LGM 2015 will play host to a collection of off-track events. In the last week of April, document sprints, hackfests and workshops will take place around the University of Toronto campus. Details will be posted here as they become available.

HarfBuzz Documentation Sprint

Volunteers are welcome! If you care about improving FOSS typography or just want to help write documentation, please join us. You can contact Nathan Willis (nwillis@glyphography.com) or write to the HarfBuzz mailing list (

https://lists.freedesktop.org/

The HarfBuzz Documentation Sprint will take place in the boardroom of the Semaphore Research Cluster (room 7020 of Robarts Library ). Directions on getting to Semaphore are available here .

Inkscape Hackfest

For three days before LGM 2015, Inkscape developers will be getting together, face-to-face, in Toronto. The Inkscape Hackfest provides an opportunity for developers who normally collaborate online to get together, talk, and solve problems.

As they put it, “Being together in one room also allows us to work on things that are harder to do on-line: designing a new plugin/extension system, teaming up to squash particularly nasty bugs, authoring better user documentation, and planning where to take Inkscape development in the future.”

The Inkscape Hackfest will take place in room 1150 on the first floor of Robarts Library ( 130 St. George St. ). More details on how to participate will be posted as they become available.

Two Workshops with Open Source Publishing: Portrait of a Community/What Happens in Canada Stays in Canada

These workshops will take place from the 27th to 29th of April. Register for the workshops!

We, the Brussels-based design collective Open Source Publishing, practice graphic design using only open source software. Along side, we see our time progressively being dedicated to the creation of our very own tools. Inspired by the vibrancy of the free and open source software community we try to inject its way of working into the world of art and design. When collaborating digitally (which is all of the time), we use a versioning system called ‘Git’. Git was initially developed to share code, so it works better for sharing text than for sharing images. That is why we have started to develop a git-based tool for collaborative design called ‘Visual Culture’. Visual Culture is a tool for sharing and publishing visual projects. It allows to view and archive and exchange the different versions of a file. Drawing from the rich culture of Free and Open Source Software, the project is developed with the ideas of collaboration, sharing and publishing at its core.

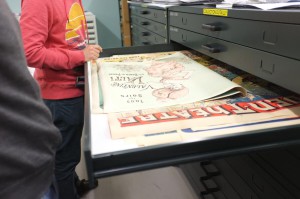

In these two workshops we propose to explore the potential of Free & Open-Source culture at large, and Visual Culture specifically as a tool and reference. We work with public archives ready to be explored and analysed, and whose contents we can copy and remix, either because they are published with an open license or because they are in the public domain.

Workshop A: Portrait of a (digital) community

This year the annual Libre Graphics Meeting (LGM) will be held in Toronto. The Libre Graphics Meeting is a conference for the creators and users of Free and Open Source graphics software. As this year will be LGM’s 10th edition we feel the need to reflect upon the LGM and the projects that take part in it. Opensource projects communities communicate mainly through digital channels, these channels are publicly accessible and archived. We propose to draw portraits of these communities by investigating their public archives.

After an introduction in the various ways OSP has visualised (programming) projects & archives up till now, and a first impression into the different projects and ‘channels’, we will create teams which use various analysis and visualisation tactics. Sources that can be used are amongst others: commit logs (lists of messages written when code is added, adapted or improved), release notes (retrospective texts after significant releases), discussions (IRC channels), mailing lists, meeting images, conference videos, etcetera. We can investigate, map and analyse them with tools like EtherCalc, Graphviz, Pattern, NLTK & OpenCV. As these tools themselves are Free and Open Source, this will mean creating a portrait of the community through its own means.

Workshop B: What happens in Canada stays in Canada (for the next twenty years)

This second workshop will look at the practice of artistic appropriation—artistic techniques such as remixing, montage, citation that are legally grouped under the term ‘derived works’. Fundamental to many forms of artistic creation, but legally strenuous, we’ll look at the legal limits (and legal paradoxes) which surround the creation of derived works. In conjunction, we will try to find out if the process of creating derived work cannot be made more understandable by tracking and visualising the procedure.

This second workshop will look at the practice of artistic appropriation—artistic techniques such as remixing, montage, citation that are legally grouped under the term ‘derived works’. Fundamental to many forms of artistic creation, but legally strenuous, we’ll look at the legal limits (and legal paradoxes) which surround the creation of derived works. In conjunction, we will try to find out if the process of creating derived work cannot be made more understandable by tracking and visualising the procedure.

OSP has had the opportunity (during a workshop in Chaumont (FR, 2013) to research and create a thorough review of the legal *status quo* around these questions. In Europe, citing, re-using or transforming another’s visual work is subject to stringent limitations. Thankfully, much more

freedom is afforded to works that have entered the Public Domain. For someone’s work to enter the Public domain though, we must wait for a very long time. Most countries enforce a period of 70 years after the death of the author. Canadian remix artists are luckier. Not only is visual citation more easily granted through the Canadian system of ‘fair dealings’ but works actually enter the public domain ‘only’ 50 years after the death of the author.

Canadian artists and designers can therefore freely (re-)appropriate works by artists born between 1944 and 1964: Frank Loyd Wright, Matisse, Kurt Schwitters, Tristan Tzara, Paul Renner, Francis Picabia, … Of special interest to OSP are Belgian makers like OSP: Paul Vizzavona and Henri van de Velde, for example. Basing ourselves on the works of these artists, we will experiment with differents techniques of re-appropriation, at the same time getting to know the Free and Open Source tools used by OSP in their daily practice. Once an artistic work starts to become a composite of earlier works, we are interested in tracking the specificities and history of its components. How and where do we log the travels and the history of a visual file? How can we display differences between images? How can we provide tools to record/explore/inscribe histories into different images / files? Of course, whatever we make in the workshops will be legal only in the Canadian context. So what happens in Canada stays in Canada—at least for the next twenty years.